Accueil > Actualités > Economie > 2025 >

The Colors of the Economy (article in english)

In a Parisian café, two presences brush past each other without ever touching. He, absorbed elsewhere, pipe between his lips; she, shoulders slumped, eyes adrift, contemplates a glass of absinthe whose frothy green evokes neither festivity nor consolation. In 1876, Degas unveils L’Absinthe. The critics erupt. For some, it is a moral warning against idleness and vice; for others, a simple observation of ordinary humanity. One spectator, scandalized by the woman’s unkempt appearance, condemns her—only to reconsider moments later.

A century and a half on, the scene is no longer interpreted solely through the lens of taste or morality, but through that of data. Thousands of contemporary viewers, invited by the ArtEmis project to record their emotions, see above all sadness (over 60%), some amusement (nearly 20%), and, for a minority, contentment (10%). These figures redraw the contours of art. They offer a way of measuring the deeper nature of works—or at least the subjective responses they elicit. By the same method, Kandinsky gravitates toward amusement or excitement, Monet toward serenity, Rembrandt toward gravity. British and Danish canvases are more often perceived as soothing than their Italian or Spanish counterparts. History itself leaves its imprint: the Spanish Civil War, the Counter-Reformation, or the great conflicts of the twentieth century shift the emotional balance, much as an exogenous shock distorts a demand curve.

Artists know their cycles, and so do their spectators. Twenty-five years after L’Absinthe, Degas paints The Blue Dancers: luminous diagonals, suspended movement, purified lines. Sadness, for viewers a century and a quarter later, is far less perceptible.

The digital era now permeates art. Connected biennales, immersive exhibitions, and online platforms track visitors’ reactions by the second. Gallery owners know how long a gaze lingers, whether admiration survives the first shock, whether curiosity evolves into desire for purchase. Art is increasingly a world of data. Emotion becomes an indicator—almost an economic variable. Works that capture instantly but fade quickly resemble fragile growth stocks. Those that establish themselves slowly yet durably evoke solid bonds. The rarest combine both: immediate impact and lasting yield. It is here, in the lineage of Monet or Kandinsky, that certain contemporary signatures emerge—capable of marrying the force of the first glance with a silent persistence.

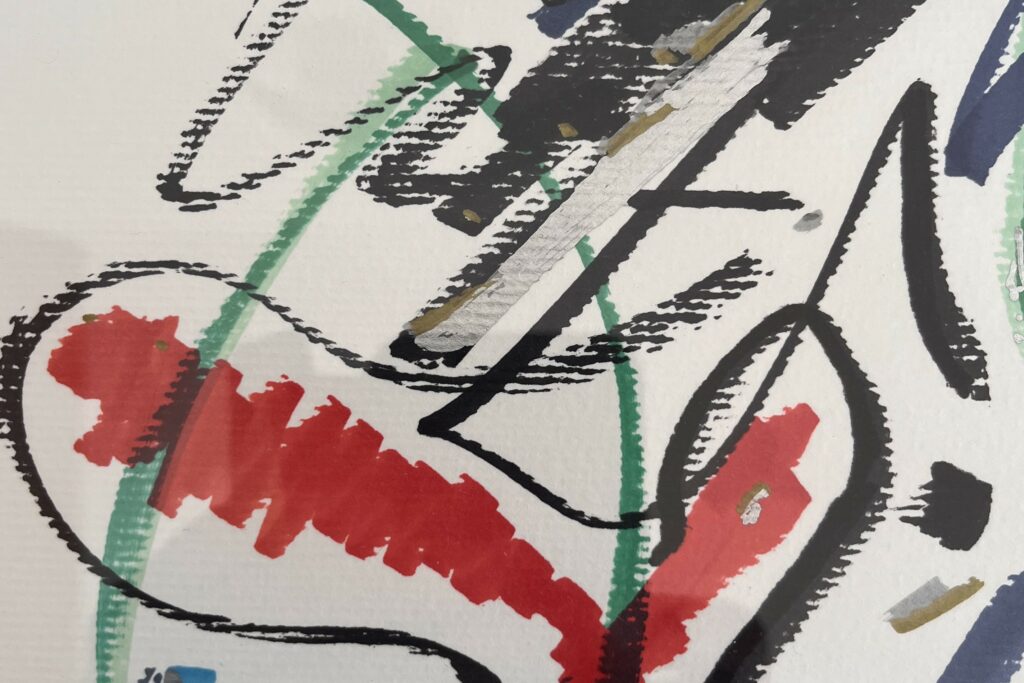

Art has always practiced rupture, both of spirit and of technique. Today, several painters draw upon the digital zeitgeist, blending color, emotional vibration, gesture, and rhythm—as in the work of Canadian artist Stephanie MacKenzie, who constructs her canvases to the tempo of chosen music. The energy of her color fields, the tautness of her lines, the breathing of empty space reveal what, in a market saturated with images, can seize and hold. It is not the brutality of an effect, but the architecture of an emotion that takes hold—like organic growth in an economic chart. The pulse of rap, techno beats, or DJs’ waves, translated into Stephanie MacKenzie’s brushstrokes and sketches, become leading indicators of societies in search of bearings.

Paintings mirror societies. Elevated economic growth subtly shifts the palette: the share of works associated with sadness declines, while contentment advances. Economic openness works in the same direction: at the end of the nineteenth century, as Britain’s foreign trade soared, the art it produced seemed to lighten, to brighten. Free trade, championed as a source of wealth, also proved a softener of mood. Today, painting is increasingly steeped in the violence of the street, in drugs, and in the grip of organized crime upon society. Yet it also expresses the search for inner serenity, for beauty beyond the darkness of the times.

Of course, to reduce art to a mere reflection of economics or society would be excessive. Emotions carry their own ineffable nuances. Yet close observation can deliver early signals. Art may well serve as a leading indicator. A sustained rise in works perceived as soothing may foreshadow renewed confidence; an upsurge in gravity, a retreat, a social tightening. Art does not announce figures—it whispers trends. L’Absinthe was the discreet thermometer of a nineteenth century torn between the intoxication of modernity and urban solitude. Some contemporary works, at times born of rhythmic brushstrokes, capture the twenty-first century in its own oscillation: the speed of attention, the slowness of assimilation.

Economists prize robust indicators; artists offer atmospheres. And in this dialogue between numbers and colors, one suspects that true economic foresight may not lie in statistical tables… but in canvases themselves.

Philippe Crevel

Crédits photos et site de l’artiste Stephanie Mackenzie

@Stephanie MacKenzie – don à l’auteur de l’article –

Site de Stephanie MacKenzie

Instagram de Stephanie MacKenzie

Suivez le cercle

recevez notre newsletter

le cercle en réseau

contact@cercledelepargne.com